Interviews

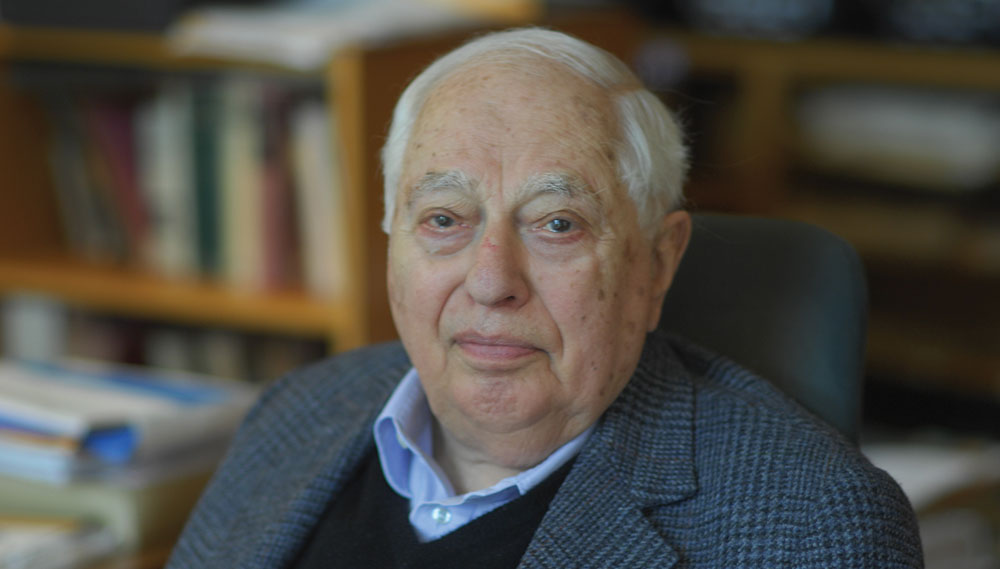

Face to Face with Bernard Lewis

The mainstream media often cites Bernard Lewis as the doyen of Middle East studies. His writing and publications are prolific, easily filling numerous shelves at most university libraries. Regardless of one’s opinion of his views, there can be little doubt over his impact on the academic study of the Middle East, as well as popular perceptions of the Muslim world.

Lewis is also one of the more divisive figures in the study of Islam and the Muslim world. His analysis and interpretation of the Muslim world, particularly vis-a-vis the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union, made him one of the most sought-after regional specialists among journalists, policymakers and political pundits. His seminal essay, “The Roots of Muslim Rage,” which appeared in the Atlantic magazine in 1990, could very well be responsible for how an entire generation of post-Cold War thinkers perceived the Muslim world.

As part of an ongoing series of interviews with influential thinkers affecting the Muslim world, I was able to sit down with Professor Lewis and learn his perspective on the rapid changes taking place in the Middle East and whether he has changed his outlook of the region as he enters his 95th year.

He agreed to meet me in his home in Princeton, N.J. one Monday morning. His small house is off a side street near the main gates of Princeton University. Upon opening the door, he greeted me warmly and led me down a hallway lined with shelves of books, opening into a large bedroom that he converted into a library with bookshelves spanning the entire room, floor to ceiling. His home certainly fit the profile of a lifelong academic approaching the century mark.

“I think confronted with the modern world or with the rest of the world, I think people are becoming aware that the Western and Islamic civilizations have more in common than apart.”

We met for almost an hour and a half, discussing a wide range of topics – from the Arab Spring to the idea of democracy in Islam. While the words he used to articulate his perspective may have been a little softer due to my presence, it did not seem that recent events have changed his thinking. Lewis’ body of work speaks for itself.

Amina Chaudary: In your often-quoted article, “The Roots of Muslim Rage” in The Atlantic, which shares a theme in many of your other works, you write: “This is no less than a clash of civilizations – the perhaps irrational but surely historic reaction of an ancient rival against our Judeo-Christian heritage, our secular present, and the worldwide expansion of both. It is crucially important that we on our side should not be provoked into an equally historic but also equally irrational reaction against that rival.” I suppose you consider that the rival is Islam, or Muslims. So my question is, after 21 years of writing the article, do you believe there is still a clash of civilizations between “our Judeo-Christian heritage” and what you say is the rival – Muslims or Islam?

Bernard Lewis: I think there were clashes. I think it was accurate in the past. There is still a confrontation, there is no doubt about that. But I think confronted with the modern world or with the rest of the world, I think people are becoming aware that the Western and Islamic civilizations have more in common than apart. It was a German scholar, C. H. Becker, who said a long time ago that the real dividing line is not between Islam and Christendom; it’s the dividing line East of Islam, between the Islamic and Christian worlds together on the one hand and the rest of the world on the other. I think there is a lot of truth in that.

©sohail nakhooda

AC: So you no longer consider it a “clash” today? That’s interesting given the wide range of influence that term has had through today. Did anything in particular change over that time period to make you say it’s no longer a clash and that there is a bit more potential for cooperation?

BL: Well I think the main thing is the growing awareness in the Christian, or should I say the post-Christian, world and the Muslim world, of these facts and of their confrontation with another world outside, a growing awareness of what they have in common. In the West nowadays, it’s very common to talk about the Judeo-Christian tradition. It’s a common term. The term is relatively modern but the reality is an old one. One could with equal justification talk about a Judeo-Islamic tradition or a Christian-Islamic tradition. These three religions are interlinked in many signification ways, which marks them off from the rest of the world. And I think there is a growing awareness of this among Christians and among Jews, and even to some extent to some Muslims. That’s happening for obvious reasons.

AC: In the same article in “Roots of Rage,” you say: “And then came the great change, when the leaders of a widespread and widening religious revival sought out and identified their enemies as the enemies of God, and gave them ‘a local habitation and a name’ in the Western Hemisphere. Suddenly, or so it seemed, America had become the archenemy, the incarnation of evil, the diabolic opponent of all that is good, and specifically, for Muslims, of Islam.” Do you still hold to the belief that Islam is at war with America?

“One could with equal justification talk about a Judeo-Islamic tradition or a Christian-Islamic tradition. These three religions are interlinked in many significant ways.”

BL: Not specifically with America but with the Western world in general for which America is rightly perceived as the leader. Muslims naturally saw Christendom as their arch rival. One point that is really important to bear in mind, particularly in addressing an American audience, and that is that the Islamic world has a very strong sense of history. In the Muslim world, history is important and their knowledge of history is not always accurate but is very detailed. There is a strong historical sense in the Muslim world, a feeling for the history of Islam from the time of the Prophet until the present day. And for most of that time, there was a confrontation between the Dar al-Islam and the Dar al-Harb. The Dar al-Harb to the East did not matter so much. The Dar al-Harb to the West was the one that mattered because this was the rival claimant. You see Christians and Muslims have one thing in common which they do not share with their other religions as far as I know. They claim to be the fortunate recipient of God’s final message to mankind. The Jewish point of view is different. The Jewish Talmud says that the righteous peoples have an equal place in paradise. The Christians and Muslims agree in rejecting that; they claim that they are the fortunate recipients of God’s final message and those who accepted will go to heaven and those who rejected go to hell. So there is a long struggle between the Dar al-Islam and the Dar al-Harb, which in effect was Christendom. This was the perceived enemy. And this has inevitably colored the perception of everything else.

AC: This Dar al-Harb and Dar al-Islam theory is very much a medieval theory that does not remain relevant today given the dramatic difference in the way nations are conceived, operated and governed between now and when the theory was originally articulated hundreds of years ago. So, you understand that the struggle is necessarily between Islam and the West. Of course we are all very familiar with the harm in creating this dichotomy of “Islam” and “the West.” Something that I discussed with Samuel Huntington and that he agreed too was the danger in attempting to establish in theory “separate worlds” that are not at all separate or divided. Do you continue to identify it in that way?

BL: From the Muslim point of view, it is between the Dar al-Islam and the Dar al-Harb. At the moment, the important part of the Dar al-Harb is the West. In the past it has been elsewhere, whether it was India, China or elsewhere. But at the present time, it’s the West, because this is the alternative, the rival. Christians and Muslims share the belief that they are the fortunate recipient of the final message.

AC: I really struggle with this citation of Muslims, and the Muslim world categorizing people in only one of two ways, as you bring up the Dar al-Islam and the Dar al-Harb. This presupposes that all Muslims or “the Muslim world” is unified in existing in viewing the world in one of two ways only. When I read the “Roots of Rage,” from my experience and based on my research, I don’t at all get that same feeling of being at “war” with America or the “Christian” world nor that the world, or Muslims, exist in this way, particularly given the deep roots of Islam within the “west.”

“One of the strengths of Islam is that it does give dignity. A remarkable feature of Islam is that it gives dignity even to the humblest illiterate peasants. It gives them a certain human dignity which one doesn’t find in other societies.”

BL: But the rage is widely expressed and very strongly expressed. I’m not saying all Muslims share it, but it is a powerful factor in Muslim public communications. That doesn’t say that all Muslims or a majority of Muslims share it. But probably of those who are articulate. The ones who don’t share it prefer to keep silent for understandable reasons. They want to go on living.

AC: Muslims go on denouncing any acts of violent or terrorism directed at the West or anywhere else, plus given the generations of Western Muslims. Granted, there are radicalized voices within Islam now waging a war, but what makes this radicalization you mention different from other religions and other sects also undergoing strains of radicalization? Isn’t this radicalizations across the board?

BL: I don’t think you see this in the Christian world. In the Christian world, as you remember, Christianity is in the 21st century, Islam is in the 15th century. I don’t mean to say that Islam is backward; I mean to say that there are certain experiences that it hasn’t gone through. Christianity had the great religious wars of the 17th century. Islam, fortunately for the Muslims, did not have that. Christianity worked out a system of toleration. Islam was always more tolerant of Christendom. If you look at the movement of refugees, in Lenin’s phrase, “the people who voted with their feet,” the movement of refugees until comparatively modern times was overwhelmingly from West to East, not from East to West. Refugees of all kinds were constantly fleeing from Christendom to the Islamic lands. Jews of course and Muslims of course, but even some Christians and the movement of refugees went overwhelmingly that way. Look at the position of Jews, the common minority shared between the two. People nowadays try to condemn it by saying that Jews and Christians in the Muslim state were second-class citizens. You must have heard that phrase. And this is used obviously as a condemnation. In modern terms, yes, second-class citizenship is a condemnation, but go back a little. Second-class citizens with citizens’ rights recognized and defended by the state and accepted by public opinion is much better than no citizenship at all, which is the fate of the rest of the world in most of its history. The position of non-Muslim minorities in the Islamic states until modern times (in modern times it has deteriorated as you know), but in modern times it was vastly better than at any time in Christendom. I always put it this way that it was never as good as Christendom at its best and never as bad as Christendom at its worst.

On the War in Iraq

AC: In 2004, Time magazine named you to its “Time 100” list and argued that, “No scholar has had more influence than Lewis on the decision to wage war in Iraq.” In 2004, you continued your outspoken support of the American invasion, stating that the war “was worth it” and that you maintain the position that Iraq could have been the opportunity to create an impact on democratizing the region. And this democracy was one that needed to be created by a closely monitored American system. We knew then that Iraq would not be a model for democracy, so were your assumptions incorrect that an American invasion would bring about “democracy” as you argued?

BL: My position on that has been misrepresented again and again and again in the media. Let me make it clear. There are two wars in Iraq. The first one was absolutely necessary and entirely justifiable. Saddam Hussein had attacked and invaded Kuwait, a sovereign independent state, it was a blatant act of aggression, and action was justifiable and necessary. I have no problems with that at all. The second one was a different matter. You remember that after that (first Gulf War), Iraq was divided. There was a Southern zone, which was more or less controlled by Saddam, and a Northern zone, which was shared between Kurds and Shiites, which worked fairly well. The Northern zone in Iraq was extremely successful. It was peaceful, it was prosperous, the schools and universities were functionally normally. Everything was going really really well. Now, at a certain point, the local leaders, the Kurds and the Arabs came up with an idea. They said that they would like to proclaim an independent government of free Iraq. Now an independent government of free Iraq proclaimed in New York or Washington or London or Paris would be meaningless. But one proclaimed in Iraq would really be meaningful. Now they made it perfectly clear that they did not want any military help. On the contrary, they said that would be counterproductive. They were perfectly capable of handling the military situation. They had complete control of the North and they had many promises of support from the South. All that they asked for was a clear statement of political support and recognition. They never got it. They asked the Clinton administration and all they got was waffle. They asked the Bush administration and all they got was waffle. Unfortunately this, I think, was the right thing for them to ask for; it would have been the right thing to give them but they never got it. And instead we had that second invasion in Iraq, which I think was a great mistake. I did not support that. And that was not the line of policy that I supported. I was in favor of giving help and recognition to their own project for an independent government of free Iraq, which was what the Kurds and Arabs in the North had proposed at the time.

AC: So in 2004, when you were making the press rounds, you’re saying your support was for not the American invasion of Iraq but for the Iraqis to build their own democracy?

BL: Helping the Iraqis. Giving them what they ask for but not more than that.

AC: I ask this just to be clear, that the perception is very much that you were one of the biggest proponents for the American invasion in Iraq.

BL: I know, that has been said again and again and again. And it is just simply not true.

AC: And, if I may, your name is often times cited as engaging with, if I may in quoting various articles, neoconservatives’ like George W. Bush and Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, and in this way you were encouraging of their push towards an American invasion in Iraq. Do you disagree with this?

BL: Well I am on good terms with Bush and Cheney, that’s true. I don’t know what you mean by neoconservatives, it’s a term used in many ways. But simply on this point, I know it is said repeatedly that I was in support of the American invasion in Iraq. It is simply not true. I was in favor of helping the Iraqis, and most specifically Ahmad Chelebi and the Kurdish leadership to set up an independent government of free Iraq. I think that would have been the right thing to do, I think it would have been successful and I think it was a great mistake not to do. The whole thing was badly handled.

On Democracy in the Middle East

AC: I came across a recent interview in 2011 to the Wall Street Journal, where you said: “We have a much better chance of establishing – I hesitate to use the word democracy – but some sort of open, tolerant society, if it’s done within their systems, according to their traditions.” For the most part, it seems you changed your position about democracy in the “Muslim world” eight years after the Iraqi failures?

BL: No, I thought so then and I think so now. The word “democracy” is a Western word obviously. It doesn’t exist in Arabic. Democratiya is a loan word. We in the Western world make the great mistake of assuming that ours is the only form of good government; that democracy means what it means in the Anglo-American world and a few other places in the West, but not many others. Muslims have their own tradition on limited government. Now in Islam, there is a very strong political tradition. Because the different circumstances, Islam is political from the very beginning. Moses led his people through the wilderness and he wasn’t permitted to enter the Promised Land. Jesus was crucified. Mohammad founded a state which soon became an empire, so that Islam from the very beginning is involved with government, with politics. And therefore there is a very clear strong political tradition in Islam. And I think the important point which I’ve been trying to get across is that Islam, from the very beginning, is strongly, clearly opposed to autocratic dictatorial government. The idea which we so often hear expressed in the Western world, that’s how they are, that’s how they will always be and they can’t do anything else. That’s nonsense. On the contrary, Islam explicitly rejects dictatorship and there are no traditions of the Prophet or passages in the Qur’an which clearly give dictators this support.

©sohail nakhooda

AC: So when we look at what is happening now in the Middle East, in Egypt and Tunisia for example, we see these indigenous, nonviolent democratic movements for change, in spite of Western intervention. These were to protest Western-backed autocratic dictators. Yet, no American, British or Western flags were burned, despite the fact that these leaders were in rule for so long against the democratic system they wanted. They were acting as less a humiliated people than a people seeking dignity. How does this square with your thesis regarding Muslim rage where you state that Muslims are a humiliated people rather than those seeking dignity?

BL: I think the most important single issue there is the Muslim awareness of history, which has no parallel anywhere else, certainly not in the Western world, where there is an overwhelming ignorance of history. Muslims are very keenly aware of the history of their community, of the history of that relationship between their community and the rest of the world. And they have had this all through the centuries and are very much heightened by modern communications. I mean now you have Muslims in the Muslim world who can compare their situations with people elsewhere and they find that very humiliating.

AC: But the issue here is that these movements represent a democratic process and is an expression of a certain type of will that is less so related to the question of humility than it is related to the question of acquiring a sense of dignity.

BL: They certainly want to acquire a sense of dignity. But one of the strengths of Islam is that it does give dignity. A remarkable feature of Islam is that it gives dignity even to the humblest illiterate peasants. It gives them a certain human dignity which one doesn’t find in other societies. One finds it in Christendom but not elsewhere in the world. And even in Christendom, it is limited. Islam does give human dignity, certainly. The point I wanted to make is that it is great foolishness to try to impose our notions of democracy. They have their own traditions.

AC: This “they” you keep referring to, do you mean Muslims? Like me?

BL: Yes, the Muslims. They have their own traditions. The important point to bear in mind is that the whole Muslim tradition is totally and unequivocally opposed to autocratic and oppressive government. This is very, very clear. Now in opposing that, we always talk about freedom in the Western world, they always talk about justice. Very often we mean the same thing. But what we do mean, what in the Western world we call human rights, in the Islamic world, they don’t talk about rights. Now they do, but in the past they didn’t. It wasn’t part of their terminology. But really it’s the same thing.

AC: But are you then arguing that it was always part of the Western terminology?

BL: No, it’s comparatively modern. It’s equivalent to Islam basically. So there is no difference. In the Western world, it begins in the 18th century, or rather late in the 17th century with the English revolution.

AC: So where do you argue there is a difference?

BL: What is it that distinguishes good government from bad government?

AC: Accountability or responsiveness to the needs of the people.

BL: Yes, you see in the Muslim traditions, it’s very clear: maintaining law and consultation, not being arbitrary and oppressive. Consultation. And also in the Muslim tradition, the power comes from within the group. I think that’s very important.

“The important point which I’ve been trying to get across is that Islam, from the very beginning, is strongly, clearly opposed to autocratic dictatorial government. The idea which we so often hear expressed in the Western world, that’s how they are, that’s how they will always be and they can’t do anything else. That’s nonsense. On the contrary, Islam explicitly rejects dictatorship and there are no traditions of the Prophet or passages in the Qur’an which clearly give dictators this support.”

On Turkey

AC: I want to talk to you about Turkey, this idea of democracy. You used Turkey at one point as being the example for the possibility of democracy in the Muslim world, but as of recently, your position has changed. Could you explain that?

BL: Well it’s what has been happening in Turkey. The country has been taken over by the present rulers and they have been very, very skillful and taking over everything and taking over control over everything and now taking control over the judiciary. They will be taking over the constitution. Unless there will be some radical change, which is unlikely, I will say the tradition of Kemalism will be dead in Turkey. And Turkey is becoming a more Islamic state, in the traditional sense.

AC: Would you consider that Kemalism itself came with a certain amount of oppression and despotism? Wasn’t that a relatively harsh or oppressive process that had to happen?

BL: Yes, Mustafa Kemal’s government was certainly authoritarian, but he had a saying which is profoundly true, I don’t remember the exact words, but what he said was that I am a dictator so that there will never again be a dictator in Turkey, and I think that was right. He felt that there were certain changes which needed to be made. He wanted to make those changes, he felt they were essential.

AC: Under the AKP party, according to Freedom House, political and civil liberties have improved in Turkey over the past 10 years. What exactly concerns you about Turkey’s transition? If the people of Turkey are freer and enjoy greater civil liberties, then why is their rhetoric of Islam of concern to you?

BL: I’m not sure that they are freer there. There are a number of prosecutions for newspapers for publishing things. There is now a sort of government takeover even now of the judiciary. No, I think that the growing government control of the press is very clear. Turkey is still not a dictatorship, there is still some freedom of the press, but I think it’s moving in the wrong direction.

AC: Is it just that the army was seen as the “arbiter” of democracy but there were also issues in that perspective as well?

BL: The army intervened a number of times.

AC: Which it has not done in the last 10 years.

BL: Which it has not done. The last time was what they called their post-modernist coup. And when they intervened, they did very discreetly and in the background and so on. The army is now under control. The judiciary is under control. You see in Turkey, they had a remarkable success story in building up a democracy. I was in Istanbul for most of the year 1950. That was the year when the government held free and fair election, was defeated and simply withdrew from power and handed it over to the opposition, without precedent in Middle Eastern history. That was a really remarkable time and it was a fascinating and rewarding experience to be there at that time. Now since then, there had been one attempt after another. What I was going to say was the army intervened, but immediately after having intervened, they restored the constitution, and they withdrew again. Now this happened three times, three times the government was beginning to go astray, trying to establish its own dictatorship. The army intervened, restored the democratic political process and immediately withdrew again. No less than three times, they did not retain power, they went out of power. The fourth time was what they called their post-modern coup. They didn’t actually do it; they just threatened to do it that time. Since then, I don’t know what’s been happening in Turkey and I’m perturbed. On the other hand, I see encouraging signs of democracy developing in other places in the Middle East. In Tunisia, in Iraq, and now in Egypt. Tunisia is the one Muslim country that does something for girls and education. As far as I know, this is the only Muslim country where this is true. There is compulsory education for girls from the age of 5.

AC: But this is also true in Iran.

BL: In Iran? I’m not sure.

AC: And in fact, I think the majority of university graduates are women.

BL: That’s true, yes. But certainly Tunisia was the first. It’s been like that for a long time and women play an important part in Tunisia. There are women in all professions. Doctors, dentists, lawyers, politicians, journalists and so on. And I think that Namik Kemal was right in saying that one of the main reasons that the Muslim world fell behind than the West was, as he put it, we deprive ourselves of the talents and services of half the population. If you put it that way, it’s very clear. How can you hope to keep up with the Western world?

On Foreign Invasion

AC: You have argued that: “If we turn from the general to the specific, there is no lack of individual policies and actions, pursued and taken by individual Western governments, that have aroused the passionate anger of Middle Eastern and other Islamic peoples. Yet all too often, when these policies are abandoned and the problems resolved, there is only a local and temporary alleviation.”

BL: Yes. That’s true.

AC: Many would argue and I’ve heard this argument many times, that the anger remains because of disrupt from foreign intervention. For example, foreign intervention in Afghanistan has created the context for religious conflict in Pakistan for the last 30 years – granted Pakistan itself has made many poor decisions along this path – yet the fact remains that sectarian tension was never this bad before the Soviet war in Afghanistan. How do you react to these current events in relation to your quote?

BL: As far as the particular grievances are concerned, obviously the particular grievances are important and solving them is a good thing, but solving them does not end the general situation. It merely makes room for another grievance. I don’t mean by that that the grievances are an excuse. The grievances are certainly useful. In most of the countries in the Muslim world today, most of them are autocratic regimes that are unpopular if not detested by their people. They need a scapegoat and for a long time the imperialist served that purpose.

AC: If you look at the broader Muslim world, particularly Indonesia, Malaysia…

BL: Well things are much better there.

AC: Right. The majority in the “Muslim world” live in a democratic, largely liberal, open society. The question here is focusing on particular cases of intervention and how those interventions have impacted the process of greater liberalization or freedom in these countries. I understand you can always blame the external aggressor, but could foreign intervention have played a greater role in creating a radical backlash?

BL: You see, the problem is that there is no foreign intervention. In the past, foreign intervention was obviously a major problem. Foreign domination, or if not domination, interference. But that has ended. There is no foreign domination; there is minimal foreign interference. The Cold War has ended. The Soviet Union no longer exists. The United States is showing minimal and diminishing interest in the Muslim world. They now have to confront their own problems. The old excuses are gone. The old justifications are gone and therefore the anger of people is turning increasingly against their own rulers. And this creates a new situation and new tensions and for the rulers, a new problem. They are still trying to use some of the old arguments but they don’t carry much weight. Blaming the imperialists nowadays is obviously absurd, as is blaming the Americans, who obviously don’t have the slightest desire to control anything in the Middle East. The American desire is to get out as quickly as possible and the general view is that now that the Cold War is over and the Soviets are no longer a problem, we have no reason to stay there, let’s get out. They will have to confront their own problems. Israel provides a useful scapegoat but it’s a limited one.

“Blaming the imperialists nowadays is obviously absurd, as is blaming the Americans, who obviously don’t have the slightest desire to control anything in the Middle East. The American desire is to get out as quickly as possible and the general view is that now that the Cold War is over and the Soviets are no longer a problem, we have no reason to stay there, let’s get out. They will have to confront their own problems. Israel provides a useful scapegoat but it’s a limited one.”

On Israel

AC: On the question of Israel, I notice a consistent theme throughout your books where you have the East and the West. So where does Israel lie? Is it an Eastern or a Western country? What are the cultural values of Israel?

BL: That’s a very interesting question. It’s both. You see, one reason which I find particularly fascinating about Israel is this. There is no such thing as a Jewish civilization. There is a Jewish culture, a Jewish religion, but there is no such thing as a Jewish civilization. The Jews were a component basically of two civilizations. In the Western world, we talk about the Judeo-Christian tradition. You could equally well talk about the Judeo-Islamic tradition because there were large and important Jewish communities living in the lands of Islam. Jews lived and flourished under Christian rule and under Muslim rule with breaks and interruptions and occasional problems. But generally speaking, Jewish history for the last 2,000 years or so has been in those two parts of the world. There are few Jews in insignificant numbers in India and China. It seemed that Judaism could only survive as part of either the Christian or the Muslim world. So when we talk about the Judeo-Christian or the Judeo-Muslim tradition, it’s important to remember that we are speaking of a Jewish component of civilization, but not in itself a civilization. What is happening now in Israel is that you have a coming together of Jews from the Christian world and Jews from the Muslim world with different cultures.

AC: Like Sephardic Jews?

BL: Well they call themselves Sephardic Jews, but that’s not the important thing. The important thing is that some come from the Muslim world and some come from the Christian world. I would call them the Muslim Jews and the Christian Jews. It sounds absurd but you know what I mean. So these internal clashes in Israel nowadays are in a sense a continuation of a clash between Islam and Christendom through their former Jewish minorities and it works out in a number of different ways. It’s fascinating to watch. And I hope they succeed in finding a compromise. At the moment, there doesn’t seem to be much sign of it.

AC: What’s one thing that most people would be very surprised to know about you?

BL: That I’ll be 95 next month. Also, most people would be surprised to know that I read detective stories.

Bernard Lewis is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. He is the author of numerous titles about the Middle East and Islam including: Islam: The Religion and the People; What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response; Islam and the West; The Muslim Discovery of Europe; and The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years.

Amina Chaudary holds a master’s degree from Harvard University in Islamic History and Culture from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She is earning a PhD at Boston University with a focus on Islam in America. She is the founder and editor of The Islamic Monthly.