Interviews

Noam Chomsky on Religion and Politics

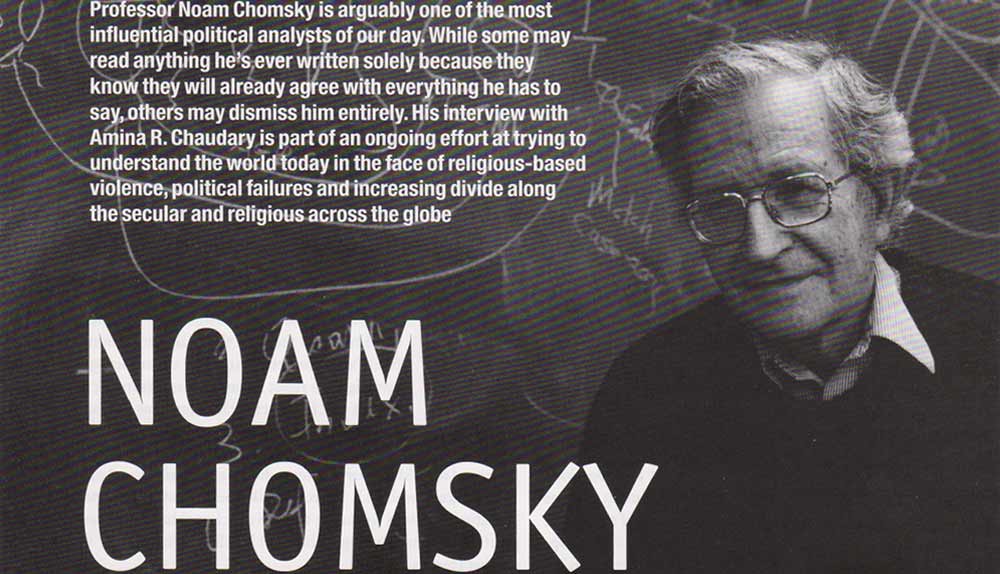

Professor Noam Chomsky is arguably one of the most influential political analysts of our day. While some may read anything he’s ever written solely because they know they will already agree with everything he has to say, others may dismiss him entirely. His interview with Amina R. Chaudary is part of an ongoing effort at trying to understand the world today in the face of the religious-based violence, political failure and the increasing divide among the secular and religious across the globe.

Noam Chomsky - scholar, activist and intellectual - has had a profound influence as a political analyst for decades. Supporters and critics alike must agree that his ideas are foundational to any progressive discussion on contemporary politics, both in the United States and abroad. He is perhaps best at assessing underlying factors in global political struggles. Yet, one cannot speak of violence and international relations without understanding primary motivators, religion being one of them.

In an interview with Samuel Huntington (Islamica, no.17), I explored a discussion based on his famous "Clash of Civilizations" thesis on the power of religion to organize and influence societies and movements, including violent uprisings. To better understand how, if at all, religion is the central motivating factor in political tensions today, I set out to discuss with Professor Chomsky these complex themes. What I discovered is that Chomsky, unlike Huntington, does not believe that religion plays a fundamental role in politics. For Chomsky, that power is muted. His concern is more with the abuse of power by the powerful than the beliefs of nations or peoples.

Ultimately, he is more concerned with social justice and speaking "truth to power." The best lesson learned is that understanding the intersection of religion and politics is far more complex than it appears to be. Religious loyalties may continue to run deep, but its influence on political goals may still be ambiguous.

AMINA CHAUDARY: Current affairs tend to indicate that a tension between and within religions, some say especially in the case of Islam, lies at the center of many conflicts in the world today. Do you think religion is exerting a greater influence on foreign policy today, both here in the U.S. and abroad? What happens when religion merges with politics - and how this is any different than other forms of identity merging with politics, such as ethnicity?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, the major problems of the world are those that appear in the most powerful states almost by definition, because whatever affects them affects everyone. And the most powerful state in the world by orders of magnitude is the U.S., and it also happens to be one of the most extreme fundamentalist countries in the world. Extremist fundamentalist religion may well have a greater hold in the U.S. on the public than say in Iran, though I've never seen a poll in Iran. But I doubt 50 percent of the population thinks the world was created 6,000 years ago exactly the way it is now. This is actually strange because way back in American history to the time of the colonists, there have been eras of religious revivalism. Most recently we see this in the 1950s, which was a big period of religious revivalism. That's how we get phrases like "In God We Trust" and "One Nation Under God." Religious revivalism picked up again in recent years. Until recent years, it was not a major force in political affairs. That has happened in the last 25 years and it is now an enormous force - fundamentalist religion, not all religion by any means. So, for example, the U.S. has often been bitterly opposed to Christianity. That painting (points to a picture) is an illustration of the hatred of U.S. leaders for the Catholic Church. It was given to me 15 years ago by a Jesuit priest. It is a painting of the Angel of Death on one side with Archbishop Romero, who was assassinated, and right below are six leading intellectuals who were murdered by an elite U.S.-run battalion. That framed the decade of the 1980s: Romero was assassinated by U.S.-backed forces in 1980, Jesuit priests in 1989 and, in between, the U.S. carried out a major war against the Catholic Church. Many of the victims of (President) Reagan's efforts in Central America were nuns, lay workers, and for clear and explicit reasons, which you can see officially stated, like the famous School of America, which trains Latin American officers. One of its advertising points is that the U.S. Army helped defeat liberation theology, which was a dominant force, and it was an enemy for the same reason that secular nationalism in the Arab world was an enemy - it was working for the poor. This is the same reason why Hamas and Hezbollah are enemies: they are working for the poor. It doesn't matter if they are Catholic or Muslim or anything else; that is intolerable. The Church of Latin America had undertaken "the preferential option for the poor." They committed the crime of going back to the Gospels. The contents of the Gospels are mostly suppressed (in the U.S.); they are a radical pacifist collection of documents. It was turned into the religion of the rich by the Emperor Constantine, who eviscerated its content. If anyone dares to go back to the Gospels, they become the enemy, which is what liberation theology was doing. So it's a mixed story. However in the U.S., the more extremist, by comparative standards, religious movements did become mobilized into a political force for the first time in history really and that's pretty much less than 25 years. It's striking that this is one of the worst periods of economic history for the majority of the population, for whom real wages and incomes have stagnated while work hours increased and benefits declined, and inequality grew to staggering proportions, a dramatic difference from the previous 25 years of very high and egalitarian economic growth and improvement in other measures of human development. There is a correlation, common in other parts of the world as well. When life is not offering expected benefits, people commonly turn to some means of support from religion. Furthermore, there is a lot of cynicism. It was recognized by party managers of both parties (Republicans and Democrats) that if they can throw some red meat to religious fundamentalist constituencies, like say we are against gay rights, they can pick up votes. In fact, maybe a third of the electorate - if you cater to elements of the religious right in ways that the business world, the real constituency, doesn't care that much about.

“Controlling Iraq is an enormous lever of world control. If Iraq was in the middle of Central Africa and exporting lettuce, they wouldn't care about it. You have to be deeply indoctrinated not to see this, and it's kind of striking about the West that the level of indoctrination is so profound that educated people can't see it.”

AC: It is interesting to see the position of religion in the U.S. How would you understand this "Western" view of Islam and could you also elaborate on this idea of secular nationalism?

NC: The attitude toward Islam is quite complex. The U.S. has always supported the most extreme fundamentalist Islamic movements and still does. The oldest and most valued ally of the U.S. in the Arab world is Saudi Arabia. By comparison, Iran looks like a free democratic society - but Saudi Arabia was doing its job. The enemy for most of this period has been secular nationalism. U.S.-lsraeli relations, for example, really firmed up in 1967 when Israel performed a real service for the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. Namely, it smashed the main center of secular nationalism, (Gamal Abdul) Nasser's Egypt, which was considered a threat and more or less at war with Saudi Arabia at the time. It was threatening to use the huge resources of the region for the benefit of the population of the countries of the region, and not to fill the pockets of some rich tyrant while vast profits flowed to Western corporations.

AC: One can see, empirically, a rise of religious expression in certain regions. Do you think the world is becoming more religious?

NC: I don't. In places where secular movements have been devastated either from within by corruption or from without by violence, it happens in many ways. The U.S. hasn't been devastated by foreign attack or suffered severe internal problems, but as I mentioned, there was a sharp decline in the economic and social fortunes of the majority, and religious extremism has grown, at least become more visible in the political arena. Something similar has happened in the Islamic world. Take the rise of Hezbollah and Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood. One major reason for their popular support is that they provide social services. If you want to feed the poor child or a poor person living in the Cairo slums….

AC: But how much do you think that is rooted in their personal profession of religion - an increase in religiosity?

NC: It varies. I once went to Egypt about 15 years ago and I met with a group of Islamic intellectuals. They were talking about the social service networks and groups and so on and so forth. I didn't know who most of them were. I came back and talked to my friend, who knew Egypt well, about the meeting and he kind of laughed and he said one of them was a Copt, one of them a Communist and they sort of recognized that their way to power and influence is to associate themselves with the one organization in Egypt that is paying attention to the needs of the poor (the Muslim Brotherhood). So I expect there is some variation, some of it sincere, some of it not, and as always, one should be pretty cautious.

AC: Do you think that religious-based groups are reacting to this idea of the "West" or rather a perceived threat to their own identity and, say for example, their Islamic heritage?

©Claudia Daut/Reuters

NC: First of all, what is this "West"? Is the West the United States - one of the most fundamentalist countries in the world and a strong supporter of extreme Islamic fundamentalism? I think there are many strains that enter into this but there is a strong tradition of democratic secularism in the world. But mostly it's been crushed, often by force, often by outside force and sometimes for internal reasons. But for a variety of reasons these tendencies have been, for the most part, marginalized. Their place is taken by Islamists for many reasons, among them providing social services, as in South Lebanon and other places. If you are a poor person with a sick child and you need help, that's where you're going to find it. Not in the government sector. And those things spread and make a difference. Part of it is religious belief and part of it is charismatic figures. There are a lot of reasons. Just in recent months, my suspicion is that there will be an increase thanks to the dramatic success of Hezbollah holding off an Israeli invasion - the first time that has ever happened. The Israeli army literally could not make it to the Litani River after a month's fighting. In fact they tried very hard in the last three days just to get a photo opportunity at the Litani River, which was in big contrast to the 1982 war, when they just got there as fast as the tanks could go. We do know just from polls that support for Hezbollah and (its leader Sheikh Hassan) Nasrallah has increased very sharply. Whether this will lead to identification with religious movements or not is unclear.

AC: If fear has served as the politics and foreign policy of the post-9/11 world and particularly as argued in the "Western" world, how do you think the Muslim world fares in this regard?

NC: The comparison is too narrow to be meaningful, quite apart from the great differences among the societies. Stimulation of fear to mobilize populations is not a novelty of the post-911 world. Take, for example, Ronald Reagan, quaking in his cowboy boots when he declared a national emergency because of the threat to U.S. security posed by Nicaragua - just two days' driving time from Harlingen, Texas - but vowed that while he recognized the enormous threat he was facing, he would be brave, like (Winston) Churchill confronting the Nazi hordes. We can trace it back as far as we like, say, to the Declaration of Independence, with its disgraceful passage about how the cruel British are unleashing "merciless Indian savages" against the peace-loving colonists, referring to "that hapless race of native Americans who we are exterminating with such merciless and perfidious cruelty ... among the heinous sins of this nation, for which I believe God will one day bring (it) to judgment," as John Quincy Adams recognized long after his own major contributions to these atrocities had ended. There are innumerable examples since, and other states are no different.

AC: Why is there more tension among the three monotheistic faiths than other major religions?

NC: Christianity … happens to be the religion of the major imperial powers. By far the greatest power and means of violence in the world happen to be in the Christian states. With regards to Judaism, most of its history has been that of repression, leading finally to maybe the worst crime in human history - the Holocaust. Since 1967 in particular, there has been a close link between Israel and the United States, but that is for secular reasons. Of course they make a cover of religion, but it has nothing to do with religion. With respect to Islam, it varies all over the map. The most extreme Islamic state is the oldest and most valued ally of the United States - Saudi Arabia. Take Saddam Hussein, who was secular, not Islamist. For a time he was Washington's great ally. In the 1980s, when he was carrying out his worst atrocities - the Anfal massacre of the Kurds, gassing of Halabja - U.S. aid was being poured into Iraq including military aid. (Former Defense Secretary Donald H.) Rumsfeld famously went there to firm up the relationship. And the U.S. actually joined the Iraqi war against Iran, in fact entering it so completely that when Iran capitulated, it was because the U.S. had entered the war. Well, it was one Islamic state against another Islamic state - the U.S. ally happened to be a secular Islamic state. Later it shifted for other reasons. In fact if you look, the power systems are pretty ecumenical. They all attack and destroy and aid and support. The relationship with the Catholic Church that I mentioned is one clear example. The decisions depend on the perceived interests of the privileged and powerful sectors who dominate policy.

AC: Why is "Islam" seen as the problem coming from the U.S. perspective?

“In the 1970s, the U.S. very strongly supported the development of nuclear energy in Iran ... Kissinger's argument was that Iran should not use up oil for energy; it should save it. It needs another source of energy - nuclear power. Today, the same people are making the opposite argument, saying Iran has plenty of oil and natural gas, and if it is trying to enrich uranium, it must be for weapons.”

NC: The world's major energy resources happen to be located in Muslim areas, right around the Gulf, so that has always been of extreme interest the U.S. as it was to Britain. If the oil wasn't there, they wouldn't care if they were animists. That is the main problem and it is mixed. That's why the U.S. sought the most radical Islamist killers it could find anywhere in the world and brought them to Afghanistan, ending up with al-Qaeda on their hands. Take Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim population. Is Indonesia a friend or enemy? Look at the history. Up until 1965, it was an enemy because it was independent nationalist. (President) Sukarno was a nationalist and was part of the non-aligned movement, wasn't following orders. In September 1965, Suharto came along, carried out one of the major massacres of the 20th century. The CIA compared it to the atrocities of Hitler, Stalin and Mao. The West was euphoric because he massacred hundreds of thousands of landless peasants and eliminated the only mass-based political party, a party of the poor as it is described by scholarship, and opened the country up to Western robbery and extortion. So he was the greatest friend ever, practically to the end. The Clinton administration described him as "our kind of guy," and meanwhile, apart from compiling a horrendous human rights record at home, he invaded East Timor and carried out the atrocities that probably come as close to genocide as anything in the postwar period, always with strong U.S. support. He was loved. If Indonesia moves more towards independence, it'll be an enemy again.

Religious comments are not the fault lines. Let's take a look at Iran. As long it was under the Shah, he was the greatest friend. It didn't matter that he was a brutal tyrant, whom the U.S. and Britain installed when they overthrew the parliamentary government. When Iran became more independent and it happened to be more Islamic, then it became an enemy. The Shah was an ally. (Former Secretary of State Henry) Kissinger's answer, when asked recently about Iranian nuclear programs, is very revealing. In the 1970s, the U.S. very strongly supported the development of nuclear energy in Iran. Rumsfeld, (Vice President Dick) Cheney, Kissinger, (former deputy Defense Secretary Paul) Wolfowitz thought it was wonderful and they were giving plenty of aid and support. Kissinger's argument was that Iran should not use up oil for energy; it should save it. It needs another source of energy – nuclear power. Today, the same people are making the opposite argument, saying Iran has plenty of oil and natural gas, and if it is trying to enrich uranium, it must be for weapons. Kissinger was asked by the Washington Post why he was saying the opposite now from what he had said then. And he answered frankly and honestly, saying they were allies then, so they needed nuclear energy, and now they are enemies, so they don't need nuclear energy. The answer runs through with considerable consistency. There are people who definitely want a clash of civilizations - like Osama bin Laden and George Bush - who are basically allies. In fact, that is commonly said by one of the leading figures of the CIA, who had for years been in charge of pursuing Bin Laden, Michael Scheuer. He wrote recently that Bin Laden and Bush are allies and if you look, you can understand why. They are essentially cooperating indirectly and they are in fact setting up a possible clash of civilizations, which otherwise didn't exist. In U.S. relations with Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Pakistan, it doesn't now exist; it's a figment of the imagination. But you can create it. It is possible to create a sectarian divide in Iraq, which is tearing the country to shreds. That was not true a few years ago. In fact a few years ago, Iraqis were saying there will never be Sunni-Shi'a conflicts here; we are too integrated and intermarried and it doesn't matter, we will stay together. Look at the country now, just after a few years of U.S. occupation. It is torn in bitter sectarian violence.

AC: What is it about the situation in Iraq? Is it ineptitude by international leaders or is it part of some greater hegemonic design?

NC: Both. The invasion in Iraq is simply a war crime, the crime of aggression, which was called in the Nuremberg tribunal the "supreme international crime," which encompasses all the evil that follows. It was for that crime, primarily, that war criminals were hanged at Nuremberg. The aggression was undertaken in the first place for normal reasons of state. Iraq is right in the middle of the world's major energy producing resources and itself has the second-largest resources in the world that are easily accessible. Controlling Iraq is an enormous lever of world control. If lraq was in the middle of Central Africa and exporting lettuce, they wouldn't care about it. You have to be deeply indoctrinated not to see this, and it's kind of striking about the West that the level of indoctrination is so profound that educated people can't see it. In fact, this truism is described as a conspiracy theory. That is the sign of deeply religious commitments that happen to be secular commitments, but they are basically a form of religious fanaticism. The Iraqis understand it but you can't understand it in the West. So yes, they are holding onto it for imperial reasons. Why is the U.S. not withdrawing? The discussion about withdrawal ignores the most obvious point, and because then they would have to concede that the U.S. entered for imperial reasons, and we are not allowed to say that. The obvious reason for unwillingness to withdraw is that a sovereign independent Iraq would be an utter disaster. It would be Shi'a-dominated, and would increase its linkage to Iran. It is already doing so in fact. There is a Shiite population across the border in Saudi Arabia that is bitterly repressed and calling for more autonomy as Iraq gains even a limited degree of autonomy. One can imagine ending up with a loose Shi'a alliance controlling most of the world's oil independent of the United States. It's inconceivable.

AC: Why is it inconceivable?

NC: I won't say it's inconceivable, but it's a major barrier to withdrawal. The U.S. knows as well as most Iraqis that the overwhelming majority of Iraqis want the U.S. to get out. The State Department's own polls show that two-thirds of the population in Baghdad wants them out immediately. For Iraq as a whole, including the Kurds, 70 percent want them out within a year. But the U.S. won't pay attention to those polls, because Iraqi independence is considered unacceptable. Iraqis overwhelmingly believe that the U.S. is building permanent military bases in Iraq, which in fact it is. The expenditures for military bases are going way up. You have to be a really educated Western intellectual not to perceive the reasons for the U.S. fear of a sovereign and more or less democratic Iraq. And it is true, it can't be perceived. Because it would require us to look in the mirror and acknowledge that we are an imperial power carrying out violence for the needs of the dominant classes here. But you are not allowed to think that, so you can't see the obvious, but it's true.

On the other hand it's also ineptitude. This must be one of the worst military catastrophes in history. It should have been one of the easiest military conquests ever. And they turned it into an utter catastrophe, for themselves as well. In fact it is such a catastrophe that they are on the verge of losing U.S. control in Iraq.

AC: Did they just underestimate? What were they trying to do?

NC: What they were trying to do is gain control of a crucial sector of the world's energy resources to expand their domination over the rest of the world. That is what they are trying to do. It happens that the particular crew in Washington, first of all they are extremely radical. They are way out at the radical nationalistic extreme. This is why they are partially criticized within the establishment. And they are utterly incompetent. Not just in Iraq; look at (Hurricane) Katrina. Every week they are shooting themselves in the foot. They are deeply authoritarian, extremist, immune to inputs from the outside like a lot of dictatorial systems, and they created a catastrophe for themselves as well. So it is a combination of rational, ugly, imperialist programs carried out by people who happened to be unusually incompetent and arrogant. Why destroy Iraqi culture? It's worse than the Mongol invasion. Did they have to do that? They just don't care. Who cares about the ragheads?

OK, so they have a culture that goes back thousands of years, so who cares? That is none of our business. It's just that "stuff happens," as Rumsfeld said. But that matters to Iraqis; they care about their culture and they care about their history. The U.S. troops were sent in with extreme brutality. They didn't have to do that. Everything they did, it was almost as if it was calculated to fail.

“Most people would be surprised to know the truth about me. They would be surprised to know that in many respects, I am one of the last conservatives. I actually take classical liberalism and the Enlightenment seriously, which is very rare.”

AC: In your critique of power, you have been highly critical of the way governments and corporations concentrate and then abuse power. How does your critique of power relate to religion and does religion lend itself to a similar power dynamic? Can religions serve to mitigate the abuse of power?

NC: Religion crosses the spectrum. You know I am totally secular. But I had absolutely no hesitation living in the Jesuit house when I visited Nicaragua in the 1980s. We didn't agree about a lot of things, but there was such a broad area of agreement that it didn't matter to me if they were praying or whatever they were doing. On the other hand, when I was growing up as a child, I had a visceral fear of Catholics that took me decades to get over because we were one of the only Jewish families in a Catholic neighborhood, which was violently anti-Semitic, and the local kids went to the Jesuit school and came out raving anti-Semites. So you know, for me Catholics were something you run away from. Religion can be almost anything you want - all over the place. And it is often mobilized for very ugly purposes, and sometimes for very humane purposes, like liberation theology. Or you can have a mixture, take say Hamas or Hezbollah. You can't deny the reasons for their support amongst the populations. You could say the same things about secular forces. What was Nazi Germany? It was both secular and deeply religious. It developed a demonic form of messianic Christianity. The German church was grotesque from certain points of view.

AC: Connecting that thought to democracy - as was the case in Nazi Germany - we can see from history that democracy can lead to tyranny. How do we understand that? How does this happen? Why does democracy fail and what must be done to safeguard against these failures?

NC: Nazi Germany was very revealing. We must remember that Germany was at the peak of Western civilization. It was the major center of the arts, literature, science and secular humanism, and regarded as a model of democracy by American political scientists. Within a few years, it was turned into a country of savage raving lunatics who perpetrated some of the worst crimes in history. That was recently noted by a famous German historian, in an article in Foreign Affairs. His family had escaped Germany to America. He very pointedly described the decline into barbarism in Germany, with phrases used in contemporary American rhetoric. He says he now fears for his adopted country. He is not saying that this place is becoming Nazi Germany; he is simply pointing out what happened in a country that was the leader of Western civilization at its peak. This is what happened in a few years there. Sometimes religion is used, sometimes other means are used. Commonly, fear is used.

The United States is probably the most frightened country in the world. In the case of the Iraq war, for example, Saddam Hussein was hated almost everywhere, certainly in Kuwait and Iran, countries he invaded. But he was feared only in the United States. He was not feared in the region. However, people in the United States were terrified of him. Half the population still thinks that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction. The government-media complex is developing the same attitude towards Iran. Look at Europe. When you talk about countries that are regarded as the greatest threats to world peace, the United States is listed way on top, far above Iran. You do the same poll here, Iran is regarded as the greatest threat anywhere. This is a frightened country, and the same was true of Nazi Germany. One of the reasons for Hitler's success was it was a population that had seriously suffered economically and that allowed him to rouse passionate fear and hatred of enemies that were about to destroy Germany, and that in fact were about to destroy Western civilization. People were genuinely afraid. That was a typical technique for mobilizing people for violence.

AC: What is one thing most people would be surprised to know about you?

NC: Most people would be surprised to know the truth about me. They would be surprised to know that in many respects, I am one of the last conservatives. I actually take classical liberalism and the Enlightenment seriously, which is very rare. Most of my opinions, not the far-reaching ones, but the short-term ones, like policy for tomorrow, are pretty much the mainstream general opinions in the U.S. and well to the left of both political parties. So I think the short-term opinions are of the majority opinion. It may be considered very radical because I am articulating it.

NOAM CHOMSKY is Professor Emeritus of linguistics at MIT in Cambridge, Mass., and is an internationally acclaimed scholar of politics, U.S. foreign policy, media and social movements. He has published more than 80 books including: most recently Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance; Failed Stales: The Abuse of Power and The Assault on Democracy; and Perilous Power: The Middle East & U.S. Foreign Policy: Dialogues on Terror; Democracy, War and Justice

AMINA R. CHAUDARY is a graduate student at Columbia University. She has worked in the field of human rights for Oxfam, Women Waging Peace and most recently for the former UN High Commissioner of Human Rights, Mary Robinson.